Following on from the Airbnb case study, here’s another example of how a business spotted and exploited an opportunity.

The $700 Problem

Neil Blumenthal was backpacking in Southeast Asia when he lost his glasses. He continued travelling for months, squinting through blurry vision, because replacing them seemed expensive and complicated. When he finally returned home and paid $700 for new frames, a question nagged at him. Why do glasses cost as much as an iPhone?

This personal frustration became the seed of Warby Parker, a company that would disrupt the eyewear industry. But the opportunity wasn't just about price. It was about recognising a broken market structure that everyone else had accepted as inevitable.

Identifying the Opportunity: Deconstructing a Monopoly

1. Questioning Accepted Prices

Most people grumbled about expensive glasses but assumed the price was justified. After all, these were precision medical devices involving eye exams, custom lenses, and quality frames.

But Blumenthal and his Wharton Business School classmates started asking basic questions: What does it actually cost to manufacture eyeglasses? Why do similar frames vary from $200 to $600? Why does adding a brand name triple the price?

Their research revealed a shocking answer: most eyeglasses cost $10 to $30 to manufacture. The retail price of $300 to $700 reflected markup, not manufacturing costs.

This illustrates a crucial entrepreneurial skill: questioning why things cost what they cost. When everyone accepts a price point as normal, there's often an opportunity hiding in plain sight.

2. Recognising Industry Structure as the Problem

Further investigation uncovered why prices were so high. A single company, Luxottica, controlled most of the eyewear market:

They owned major brands like Ray-Ban and Oakley

They owned retail chains like LensCrafters and Sunglass Hut

They owned the second-largest vision insurance company

They manufactured frames for designer brands like Prada and Chanel

This vertical integration meant Luxottica controlled design, manufacturing, distribution, and retail. There was no real competition, no price pressure, and no incentive to lower prices.

The opportunity wasn't just about selling cheaper glasses. It was about breaking a monopoly by controlling a different part of the value chain.

3. Observing Changing Consumer Behaviour

By 2010, several consumer behaviours were shifting:

Online shopping was becoming mainstream and trusted

Millennials were questioning traditional retail markups

The success of companies like Zappos proved that people would buy fit-sensitive products online

Social media made it possible for new brands to reach customers directly

The Warby Parker team recognised that the same generation comfortable buying shoes online would buy glasses online. If someone solved the try-before-you-buy problem.

4. Spotting the "Jobs to Be Done"

Through customer interviews, the founders identified that buying glasses involved several distinct "jobs":

The functional job: correcting vision

The fashion job: looking good

The convenience job: easy purchasing process

The financial job: not overpaying

The social job: feeling smart about the purchase

Traditional optical retailers excelled at the functional job but failed at almost everything else. Designer brands handled fashion but at premium prices. This gap represented the opportunity.

5. Learning from Adjacent Industries

The team studied how other industries had disrupted traditional retail:

Zappos had made shoe buying convenient with free shipping and returns

Dollar Shave Club had turned commodities into brands with personality

TOMS had proven that customers would pay for companies with social missions

Warby Parker borrowed proven innovations from other categories and applied them to eyewear. This cross-industry pattern recognition is a powerful way to identify opportunities.

The Business Model Innovation

Warby Parker's opportunity identification led to several business model innovations:

Direct-to-consumer distribution. By cutting out retail locations, insurance companies, and middlemen, they could sell glasses for $95 that compared to $400 retail options.

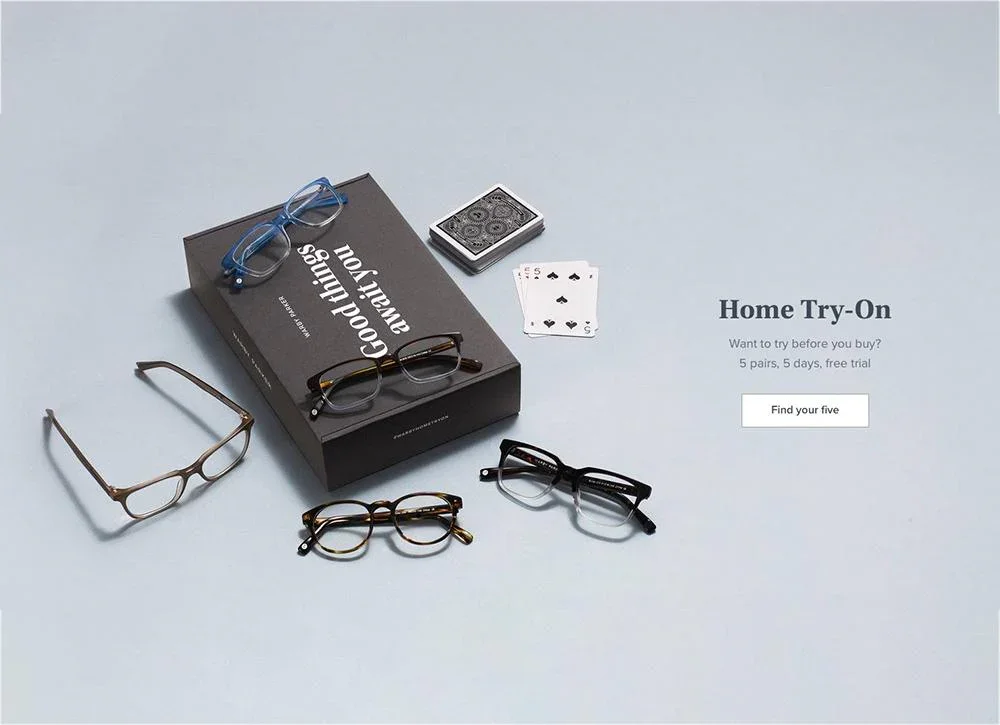

Home try-on programme. Customers could order five frames to try at home for free. This addressed the main objection to buying glasses online while creating a fun, shareable experience that generated social media buzz.

Vertical integration done differently. While Luxottica controlled the traditional supply chain, Warby Parker built their own manufacturing relationships and designed their own frames. They controlled what mattered: product and customer experience.

Buy-a-pair, give-a-pair model. For every pair sold, they distributed a pair to someone in need. This wasn't just corporate social responsibility. It was a core part of the proposition that resonated with millennial values.

The Validation Process

The founders validated their opportunity before fully launching:

They started small. Rather than building a huge inventory, they launched with a limited collection and a waiting list. When the waiting list hit 20,000 people before launch, they knew they'd found something.

They measured everything. Home try-on conversion rates, social media engagement and customer acquisition costs. Every metric was tracked to validate that the business model worked.

They iterated quickly. Early customers complained about the website experience, so they redesigned it. Some found choosing between five frames to be stressful, so they added tools to narrow down their selections. Each improvement was based on observed customer behaviour.

They tested retail cautiously. Despite being an online brand, they eventually opened physical showrooms when data showed customers wanted to browse larger selections. But they designed these as experience centres, not traditional retail stores.

The Obstacles That Validated the Opportunity

Like Airbnb, Warby Parker's challenges confirmed they were onto something big:

Luxottica could have crushed them. The incumbent had every advantage. Capital, scale, brand recognition, retail locations. But their business model was so entrenched and profitable that they couldn't match Warby Parker's prices without cannibalising their existing business. Classic disruption theory in action.

Sceptics said it wouldn't work. Industry veterans insisted people would never buy glasses without trying them on in person, that customers needed expert help, that premium brands were unbeatable. Every objection proved wrong.

Traditional competitors stayed traditional. Even as Warby Parker grew, most competitors maintained high prices and old retail models. This allowed Warby Parker to grow largely unopposed for years.

Beyond the Initial Opportunity

The eyewear opportunity opened doors to adjacent opportunities:

They added contact lenses, leveraging the same direct-to-consumer model. They expanded into eye exams via an app and partnerships with optometrists. They built a broader lifestyle brand extending beyond eyewear.

But they also recognised limitations. When early success led to requests for sunglasses, watches, and other accessories, they focused on eyewear. Knowing which adjacent opportunities to pursue and which to ignore is as important as identifying opportunities in the first place.